Introduction

“As regards Ireland, our feelings were curious… We intended as good Protestants and Loyalists to keep the papists under our feet. We impoverished them, though we loved them, and their religion by its doctrine of submission and obedience unintentionally helped us, yet we were convinced that an Irishman, whether a Protestant or Catholic, was superior to every Englishman, that he was a better comrade and physically stronger and of greater courage” – John Butler Yeats, Early Memories

Academic discourse concerning W.B. Yeats’ politics has preoccupied itself with Yeats’ sympathy for 20th century right-modernist regimes, particularly Italy under the paternal ambit of Benito Mussolini. In ‘Passion and Cunning: An Essay on the Politics of W.B. Yeats’, Conor Cruise O’Brien submits that Fascism was characteristic of Yeats’ worldview. Grattan Freyer concurs in his work W. B. Yeats and the Anti-Democratic Tradition. In contradistinction is Elizabeth Cullingford’s Yeats, Ireland and Fascism, a text that idiosyncratically attributes liberal views to Yeats – Freyer ably refutes her position in the closing chapter of his book.

But this essay does not concern Yeats’ relation to the Right. Rather, a more subdued tendency in Yeats’ politics, and broader disposition, is the subject of focus. I refer to Yeats’ distaste for post-Famine Ireland’s emerging Catholic middle class, arguably the most dynamic strata of that epoch in Irish history.

The paucity of attention his hostility has received is lamentable. Certainly, the Synge debacle and Yeats’ contribution to the mid-1920s debate concerning divorce has aroused academic interest, but near-always in isolation – even if mutually linked to a common causal factor. This root is inevitably identified as a noble commitment to freedom of expression; Freyer’s imputation of ethno-religious motivations is thus a welcome anomaly.

Though an over-emphasis on the politics of literati and poets is typical of jaded literary critics with a penchant for fresher poontang, demonstrating Yeats’ antipathy to the Catholic middle class is not a fruitless activity. Comprehensive cognisance of his convictions regarding Irish petit-bourgeois Catholics disrupts our view of Yeats as an artistic representative of, and poetic conduit for, the Irish nation.

Consequently, his unsavoury views are trenchantly suppressed by a clandestine coterie within the Irish tourism board. Although their goals are naturally hidden from the general public’s limited gaze, a panoramic perspective would indubitably reveal that they aim to ensure the subsistence of the Yeats myth (the author of this essay intends to smash this idol).

To wind up the misidentification of Yeats with the Irish nation is to risk losing the stream of dumb Yankee tourists so pervasive in the Pale and Irish hinterland. The surreptitious agents of this conspiratorial intrigue cannot abide by this. For the loss of revenue will lead to a lower budget for the board, which may in turn risk their salaries or even their jobs. Their Celtic Tiger McMansion in Sandyford is contingent on the efficacy of this psyop.

There is a widespread view of Yeats et al. as wide-eyed romanticists, their imaginations bewitched by rustic folktales recounted by rare native stalwarts of the older, purer Gaelic inheritance; an inheritance expunged by their very own ancestors. But for this to possess veracity, an about-face must have occurred. A break from the centuries-old haughty snobbery of the Ascendancy vis-à-vis the Gael.

This piece should be regarded as a mere codicil to D.P. Moran’s ‘Philosophy of an Irish Ireland’, a work which impugns the Anglo-Irish refuse that regrettably reigned as the hegemons of this Island – Royalist Englishmen and High Gaelic poets alike were forthright in their admonishment of the Southern planters. And it is a quote contained therein that epitomises Moran’s critique:

“We are proud of Grattan, Flood, Tone, Emmett, and all the rest who dreamt and worked for an independent country, even though they had no conception of an Irish nation; but it is necessary that they should be put in their place, and that place is not on the top as the only beacon lights to succeeding generations. The foundation of Ireland is the Gael, and the Gael must be the element that absorbs.”

Irish Catholics Under the Ascendancy’s Gaze

“Molyneux’s argument entered murky waters when it came to ‘origins’: if there had been an ancient contract between the English Crown and the Irish nation, it was a nation that Molyneux’s own ancestors had subsequently deprived of its property and civil rights” – R. F. Foster, ‘Modern Ireland, 1600-1972’

It’s rather fitting to open this essay with a quote from W.B. Yeats’ Father, John Butler Yeats. For not only did this man shape, along with Fenians like John O’Leary, the purview of the poet as a young man; an imbued perspective, even if departed from at times, that adumbrated his later positions on an array of matters ranging from freedom of expression to divorce.

More importantly, the cited extract encapsulates an ambivalence toward the native stock of Ireland that was not merely delimited to those who shared Yeats’ surname, extending further to the wider Anglo-Irish ascendancy. A paradoxical sentiment conferred intergenerationally which regards the Catholic Gael as apish, yet a repository of creativity; as fellahins bereft of history, yet inheritors of a grand, mystical past littered with heroes ranging from Fionn Mac Cumhaill to Cú Chulainn.

Moreover, J.B. Yeats’ adduced statement touches on an effaced strand of the Anglo-Irish volksgeist: quasi-separatist hostility to England’s overreach into Ireland’s affairs. Anglo-Irish distrust of England reached its apotheosis in the period preceding the Act of Union. While ‘Grattan’s Parliament’ may have marked a high point, its roots can be traced back to the years preceeding the Treaty of Limerick – thereafter Irish Catholics were reduced to a period of political impoverishment. D.P. Moran aptly states: “[a]fter the fall of Limerick, the country was leaderless, soldierless, without any effective powers of resistance”.

The situation was the inverse for the emerging ascendancy, yet an anxious distrust of the mother country, England, paralleled their growing power as an elite ethno-religious caste. R.F. Foster notes that Anglo-Irish separatism was a post-Williamite War phenomenon: “[t]he point to be made is that ‘patriot’ politics have their origin in the raucous tones of the post-war Protestant interest, not in the development of Grattan’s oratory three-quarters of a century later”.

However, it should be noted that a premonition of the later Anglo-Irish quasi-separatist tradition is to be found by the mid-17th century. Patrick D’Arcy, an Irish Catholic Lawyer and member of the Kilkenny Confederacy, prefigured Grattan et al. with his Argument against Poynings’ Law, published 1643, which was summarised as stating that no English statute can be enforced upon Ireland unless enacted by an Irish parliament.

Ireland has produced a disproportionate number of protectionist theorists. The leading progenitor of the American System, Matthew Carey; his son, Henry Charles Carey, who was Lincoln’s economic advisor; D.P. Moran, better known for his ability to induce rage among West Brits to this day, was also a keen advocate of protectionism; Tom Kettle possessed protectionist sympathies; Fr. John Fahy, the priest who openly called for Dev’s execution, became a protectionist post-war.

An astute reader will surely have noticed that two names have been omitted from this paragraph: William Molyneux and Arthur Griffith. One being the progenitor of the protectionist tradition, the other its most noteworthy standard bearer. Although opposed to England’s restrictions on Irish trade, and thus an ostensible free-trader, Molyneux’s commitment was guided by the self-interest of Dublin’s manufacturing base, rather than a belief in laissez-faire trade.

His concomitant commitment to economic liberty, greater political autonomy, and the premium he placed on Ireland’s manufacturing sector allows one the latitude to plausibly speculate that he would have made common cause with later protectionist theorists had it been in Ireland’s interest for tariffs to be in place. Afterall, even Friedrich List subscribed to the contention that barriers to trade were appropriate only in certain material circumstances.

Molyneux was typical of the Anglo-Irish patriots at the precipice of the 18th century – the century of Swift and Berkely, and for the Gael a century branded best by Daniel Corkery, who denominated it the century of ‘Hidden Ireland’. Other than his friendship with John Locke, Molyneux is primarily remembered for his polemic against the English subversion of the Irish woollen industry.

With respect to its competitors, England ensured its economic efficacy via high tariffs and spreading intentionally fallacious free-trade propaganda. Its modus operandi differed with regard to its colonies. Britannia’s foreign satrapies were intentionally industrially retarded by inequitable legislation. To illustrate, “a ban was imposed on the imports of superior Indian cotton products (‘calicoes’), debilitating what was then arguably the world’s most efficient cotton manufacturing sector”.

Likewise, it was clear to the Anglo-Irish industrial magnates that Ireland too was on the cards for intentional sabotage by Perfidious Albion. Molyneux’s ‘The Case of Ireland’s being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated’ conveyed his written protest of England’s overreach – the text is notable for the dictum: “no parliament but an Irish one can properly legislate for Ireland”.

The Anglo-Irish of the 1690s feared that the English parliament was seeking to quash the Irish woollen industry. Anticipating allegations that self interest undergirded his text, Monlyneux states in the preface: “I have not any concern in wool, or the wool-trade” – that he felt it necessary to disclaim this demonstrates the centrality of Ireland’s wool industry to Anglo-Irish separatist concerns.

Arthur Griffith, whose protectionist bona fides need not be stated, praised Molyneux: “When Molyneux wrote his famous book asserting the independence of the kingdom of Ireland and the responsibility to the Irish people alone of the Irish Parliament, he was boycotted by the respectable people, and the hangman publicly burned his seditious book, but his ideas no hangman could burn, and they remained secretly working in the minds of the English-speaking Irish”.

However, Molyneux’s efforts were made null and void with the advent of the Wool Act 1699, which marked the death knell of the Irish woollen industry. In his preface to Friedrich List’s National System of Political Economy, the contemporary Irish Nationalist scholar Francis O’Beirne states: “the purpose of the Wool Act of 1699, which prohibited the export of Irish wool to England, was to kill off the then superior Irish wool industry”.

The impact of the Act was devastating. That said, its detrimental impact was limited to “Irish” Protestants. Few Irish Catholics, many of whom were reduced to coolie status by the late 17th century, had financial interest in the industry. Patrick Weston Joyce, in ‘A Concise History of Ireland’, says of the Act’s ill-effects:

“This was the most disastrous of all the restrictions on Irish trade. It accomplished all that the English merchants looked for: it ruined the Irish wool trade. It is stated that 40,000 of the Irish Protestants were immediately reduced to poverty by it; and 20,000 Puritans left Ireland for New England.”

Unfortunately, Molyneux’s separatist politics were coupled with an egregious, and likely intentionally duplicitous, de-emphasis of our island’s native stock. Molyneux derived his argumentation from John Locke and Hugo Grotius, and he contended, in line with their contractual polemic against the authorities of their time, that the English parliament’s legislative interference constituted a contravention of the ur-rights of Irishmen.

But it must be inquired, which people is he speaking of when he bears the mantle of Ireland’s purported atavistic rights in defiance of England? As contemporary discourse and rhetoric demonstrates, Irishness is contestable. Our enemies seek to redefine it in a manner absent of substance. Irishness, for them, is a nominal self-identification that merely denotes one’s birthplace or citizenship.

Rather, national identity is a unity of consciousness underpinned by a confluence of factors – linguistic, mythical or religious, racial, shared ancestry in a circumscribed geographic area – that engender it in the course of history. Thus, the reduction of national identity to one’s capricious will or to an accident of birth is an offensive affront that betrays one’s ignorance of how nations germinate.

The denial of our people’s existence is by no means a phenomenon exclusive to the 21st century. In a similar vein to the rhetoric of Ireland’s malignant NGO-Gombeen strata, Molyneux denies that the Gael comprised the majority of the populace, thus allowing him to assert continuity between the ancient rights of Anglo-Saxons and the faux-Irishmen of his strata: “The great Body of the present People of Ireland are the Progeny of the English and Britains, that from time to time have come over into this kingdom; and there remains but a mere handful of the Ancient Irish at this day, I may say, not one in a thousand”

.

Griffith’s exaltation of Molyneux, and his identification of Molyneux’s co-ethnics as “Irish”, epitomises a problematic pluralist current that is near ubiquitous amidst republican circles – that not even the standard-bearer of right-republicanism, Griffith, was abreast of this is telling. Countess Markiewicz, irrespective of her many faults, must be commended for her appraisal of Griffith:

“Mr Griffith most certainly was a sincere patriot in those days, most certainly he had thrown in his lot with those who were willing to sacrifice much for Ireland. Also, he had studied much. But he had never approached the subject from a Gaelic point of view […] Mr Griffith saw Ireland merely free politically, possibly Gaelic speaking, but there his idea of the rights of Ireland to build up her own civilisation on Gaelic roots ceased”

For a lucid evaluation of Molyneux we must now turn to an Irish writer whose corpus is marked chiefly by its mordant tone. A discerning figure, for whom the edifice of republicanism, with its vaunted anti-sectarian exterior coat of paint (the gay pride colours, naturally), tempted a corrosive polemic, written with a peculiar pen filled with acid rather than ink.

I of course am referring to D.P. Moran, the man whose neologisms (‘West Brit’ especially) still induce a paroxysm of ancestrally derived horror among “Irish” Protestants – one poor unfortunate victim, a formerly virile Avoca patron and stalwart of Leinster Rugger, was left so psychologically damaged after Dáibhí Ó Bruadair called him a ‘West Brit’ that he was found by his Filipino wife muttering “Portadown… Portadown… Portadown” in the corner of his semi-D Rathgar gaff.

Moran, unlike Griffith, was not hypnotised by the patriotic pretence of Molyneux, Swift, and Grattan. He concedes that there was “some spirit, some nobility, a little genius […] in the movement commenced by Molyneux and carried to success by Grattan”. But he rejects it on grounds that it was not fundamentally Irish; the aforesaid bore greater relation to liberal-minded English parliamentarians than to the nation they claimed to represent.

He rightly discerns that the twilight of the Gaelic social order, and of the Bards that were its intellectual spokesmen, in the 17th century was sine qua non for the Anglo-Irish usurpation of our island’s intellectual life. Destitute of intellectuals, who left in the Irish camp could speak out against the subversion that was taking place? Moran states:

“The spirit of Molyneux and Swift – that same spirit which Grattan apostrophised, the spirit which 99 out of every 100 of us still look up to as our polar star – was the death of those elements of the Irish race that could have defied the attacks that were to come. It started the spirit of English civilization and English progress in our midst, and the Irish race, ceasing to think for itself, has since persistently mistaken this for the spirit of the Irish nation.”

An antagonistic attitude toward the native Irish permeated the writing of later Ascendancy literati and intellectuals. I have already explored how George Berkeley militated against our ancestors alleged laziness – “an innate hereditary sloth”, he opined. Swift did not conceal his nationality, he admitted that he was an “Englishman born in Ireland”. And not an Englishman of Aodh de Blacam’s breed, for whom Ireland is the canvas upon which romantic anti-modern fantasies are to be projected. Moran notes that Swift “regarded Irishmen with contempt”.

Returning to Yeats, though he was born a century after Swift’s passing and half a century after Grattan’s demise, and thus one would expect the enmity toward Catholics to have become marginal and passé, rancorous feelings were nevertheless imbibed from a young age by him and his Church of Ireland peers.

In ‘Reveries over Childhood and Youth’ Yeats recounts his early years in Sligo, where he routinely hoisted and, at night, hauled down the ‘Union Jack’ on his Grandparent’s property, taking great care to conscientiously fold it. Grattan Freyer notes that his nascent ideal was martyrdom in the course of fighting Fenians. Freyer captures the general attitude of his milieu vis-à-vis the natives: “Everyone he knew in Sligo at this time despised Catholics or nationalists”. Interestingly, and reminiscent of the aforementioned Anglo-Irish “patriots”, they “all disliked England”.

Maturation allowed Yeats to encounter the writings of the most articulate members of his ethno-religious caste. His Toryism was not derivative of the Irish Jacobites – he looked to those who descended from their enemies for ideological muses; the parallels to Burke are obvious. Freyer states: “There were four eighteenth-century writers who seemed to embody his new-found Toryism […] Berkely, Burke, Goldsmith and Swift”.

It is transparent that Yeats’ chief intellectual debt was owed to the foremost representatives of a group, that he too belonged to, that profited from the repression and dispossession of the Irish.

Heroic Ireland, or The Politics of Cultural Despair

“Ireland’s civilisation in the days of Red Hugh – just before its overthrow – has been likened to that of Homer by Standish O’Grady” – Aodh de Blácam, Heroic Ireland

Prior to exploring the events that re-ignited the anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment of his youth, it is pertinent to pre-emptively tackle the obvious retort that Yeats was enthralled with the Irish peasantry’s weltanschauung, and consequently cannot be considered anti-Irish. A worldview that had the potential to act as a bulwark against that pernicious phenomenon, Whiggery, which Yeats regarded as a nemesis to his own Tory sensibilities. For Yeats, the Whig was in possession of a:

“levelling, rancorous, rational sort of mind

that never looked out of the eye of a saint

or out of a Drunkard’s eye”

The intention of this essay is not to admonish Yeats specifically. Rather than treating his views as sui-generis or as an anomaly amid a stock that had ameliorated its ways, Yeats’ hostility toward the Catholic middle class – which will be convincingly demonstrated in the next section – was a microcosm of a broader current in Anglo-Irish circles. Put differently, the aim of this essay is to verify the contention that there is no fundamental disjunction between the views of Molyneux, whose outlook was typical of the Ascendancy, and Yeats – bar the latter’s bouts of romanticism.

If Yeats’s perspective was in line with Molyneux, then he equally paralleled a more novel tendency borne from his epoch, which I have touched on to some degree thus far. Sparked by the re-emphasis on Irish mythology in the latter half of the 19th century, it resulted in an oscillation of attitude among Anglo-Irish literati toward the Catholic peasantry, a people formerly subject to their haughty snobbery.

The juncture of European history between the late-19th century and the spring of the last century engendered exhaustion among the discerning – artists were especially susceptible, see: Lewis, Yeats, Pound, Hulme, and so on. Abhorrence of the modern world’s vaunted achievements and its assertion of superiority above every age heretofore is the common denominator of this spiritual cadre. They longed for an escape from the clutches of industrialism, materialism, rationalism, and the omnipresence of money-power.

For Tolkien, distaste for modernity and nostalgic celebration of the medieval world impelled him to contrive a realm of fantasy; for French ersatz-Rightists and syndicalists – such as Sorel and Barres – spiritual revolt engendered Fascism. In contradistinction to both, the Anglo-Irish sought out the intergenerationally transmitted folk-tales of rustic Gaels and the epics, especially the Táin Bó Cúailnge, of Ireland’s illustrious past. They believed that such texts, if interpreted allegorically, imparted a heroic worldview, the direct antithesis of the prevailing zeitgeist.

Once viewed as a people “wedded to [the] dirt” (Berekely’s words, not mine), the Irish were transfigured in the Anglo-Irish psyche as noble savages. This shunt in attitude was inaugurated by Standish James O’Grady; he was christened a “fenian unionist” by Lady Gregory. Ernest Augustus Boyd remarked: “It is with a peculiar sense of appropriateness, therefore, that we may salute in Standish James O’Grady the father of the Literary Revival in Ireland”.

Hibernophilia in the O’Grady clan can be traced back to his elder cousin, Standish Hayes O’Grady – his scholarly temperament contrasts with the penchant to popularise that distinguished the younger, more famous James O’Grady. According to Freyer, the latter “knew only slight Gaelic himself, but he was a careful researcher who knew how to profit from the work of others, especially his cousin, Standish Hayes O’Grady”.

Unlike Hayes O’Grady, whose encounters with the local Catholic Irish catalysed his love of the language and the people that produced it, Standish James O’Grady’s decision to celebrate the virtues of the Gael was impelled by “some chance reading on a rainy day in the West of Ireland” – that it was borne from an aloof perusal of books, rather than firsthand experience, is telling.

Yeats was influenced by both men. Angela Bourke states: “Standish Hayes O’Grady’s Tennysonian retellings made the gods and fighting men of early Irish literature vivid and active in the imaginations of W.B. Yeats, George Russell (‘Æ’) and […] James Stephens”. In his twilight years, Yeats acknowledged the debt his rebuke of individualism and cosmopolitanism owed to Standish James O’Grady. If not for O’Grady’s popularisation of “the legends of pre-Christian and Heroic Ireland” would Yeats have penned that august third stanza of ‘Under Ben Bulben’?

“You that Mitchel’s prayer have heard

‘Send war in our time, O Lord!’

Know that when all words are said

And a man is fighting mad,

Something drops from eyes long blind

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace”

As well as being a purveyor of Gaelic myth, Standish James O’Grady was a pessimistic apologist for his caste, the Anglo-Irish landlords, whom he regarded as “the best class in the country, and for the last two centuries have been”. An opponent of nationalism and democracy, he believed that the landlords were too inflexible, destined to transmute into inert carcasses as the “great modern, democratic world rolls on with its thunderings, lightnings and voices, enough to make the bones of your heroic fathers turn in their graves”.

Although I diverge from his praise for the landlords, I must concede that his gloomy description of a prospective Irish Republic came to pass, albeit in a tamer form: “If you wish to see anarchy and civil war, brutal despotisms alternating with bloody lawlessness, or, on the other side, a shabby, sordid Irish Republic, ruled by knavish, corrupt politicians and the ignoble rich, you will travel the way of égalité”.

O’Grady’s politics underwent a radical alteration by the turn of the century. After 1900 he frequently penned essays for Leftist publications such as ‘The Irish Worker’ and ‘The New Age’. Anarchist and Socialist ideas were digested by O’Grady via the works of Charles Fourier and Peter Kropotkin. His intellectual conversion to Leftism compounded with his earlier interest in pre-Norman Gaeldom and a new-found interest in ancient Hellenes – these pillars of his thought synthesised in a posthumously published intellectual-Parthenon, Sun and Wind, wherein he advocates for a restructuring of Irish society along the lines of Ancient Greece.

Rather than inwardly acquiesce to the fate of his people, O’Grady opted for flight into the arcane and the fantastical. It was symptomatic of a refusal to properly cope with the waning status of the Anglo-Irish, which was at this point assailed by a self-confident and bellicose Irish Catholic middle class.

That a disproportionate number of Protestants were stalwarts of the ‘Irish Literary Revival’ is no accident. The overview of O’Grady’s views suffices to prove that one’s interest in Irish mythology does not prevent one from holding fidelity to politics which are antithetical to Irish interests. Without engaging in baseless conjecture, it is plausible to contend that the Anglo-Irish desire to immerse themselves in the folk-tales of their tenants derived from status-anxiety and a sub-conscious collective fear that an Spailpín Fánach would one day actualise his retribution – as opposed to genuine fondness for the Irish people.

A statement by Yeats in Reveries over Childhood and Youth demonstrates that he too was not immune to the seductive power of romanticist fantasies: “I, who had no politics, was yet full of pride, for it is romantic to live in a dangerous country”. Yet his submission to the spirit of the age was not destined to last for long. With a zeal that would make his ancestors proud, Yeats threw down the gauntlet and faced off against the Irish Catholic middle class.

W.B. Yeats’ Janus Face

“To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of all past dissension and to substitute the common name of Irishman in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – these were my means.” – Wolfe Tone

One should conceptualise Yeats’ mutating relationship with nationalism as a series of crises, each of which incrementally accentuated the cleavage between Yeats and the socio-economic-religious base of Irish nationalism: the Catholic middle class.

His initial foray into Irish nationalist circles resulted in an idealistic period of starry-eyed fidelity to the Fenian John O’Leary. O’Leary was an appropriate mentor. His conversion to Irish nationalism stemmed from his encounter with the poetry of Thomas Davis; that art was his entry point is fitting given who he’d later mentor. Yeats’ dictum that “there can be no fine poetry without nationality” was an echo of ideas he had earlier assimilated in O’Leary’s Leinster Road home.

We can picture Yeats dutifully listening to the veteran Fenian waxing lyrical about Tone and Emmet’s endeavour to bridge the ethno-confessional gulf between Catholics and Protestants. Yet the 1900s were to have an iconoclastic impact on Yeats: disabusing him of Republican pluralism, renewing an awareness of his ethno-religious background, and restoring that prejudice of his youth toward the natives of Ireland.

Even as late as 1901 Yeats inveighed with rancour against England, as attested to by F.R. Benson. Arthur Griffith, later a nemesis of Yeats, praised him, stating: “We look to the Irish National Theatre primarily as a means of regenerating the country”. Yet Griffith’s disposition altered to one of unmitigated acrimony toward Yeats and the ‘Irish National Theatre’ following the opening of J.M. Synge’s In the Shadow of the Glen in 1903.

The play’s depiction of an unfaithful Irish woman spawned controversy among Catholic nationalists, who regarded it as immoral. Even Protestants were dismayed; Douglas Hyde and Maude Gonne left in protest. Griffith savaged the play in The United Irishmen, and in his public correspondence with Yeats he cast disbelief that any Irishwoman “could possibly behave as Synge’s Nora Bourke did”. Griffith could not have foreseen that Irish women would become renowned globally for their self-desecration merely a century later. The Irish race bereft of Catholic paternalism is a terrible thing.

Controversy reached its apotheosis following the opening of The Playboy of the Western World in 1907. The Freeman’s Journal admonished the play as slander against the Irish peasantry. Griffith abhorred its foul language and described it as a “vile and inhuman story”. Featuring patricide, it incensed the wrathful passions. This time Catholics rioted in opposition.

Yeats’ public apologetic became famous among Dublin’s literati circles owing to the virility and courage of his speech. Like most artists on the defensive he appealed to the liberal verity of freedom of expression, arguing that art must portray the ‘Divine and the Decay’. Henceforward, for the duration of his life, Yeats consistently conceived of himself as a lone voice of reason amid the thrall. The fallout of the most controversial episode in the Abbey’s history buttressed his anti-democratic convictions.

Yeats never forgot nor forgave Griffith’s invective. Four years later he penned ‘On Those That Hated ‘The Playboy of the Western World’’, a poem whose single stanza references Griffith’s physical deformity and his unrequired romantic longing for Maud Gonne – was everyone in Dublin simping for this beor?

“ONCE, when midnight smote the air,

Eunuchs ran through Hell and met

On every crowded street to stare

Upon great Juan riding by:

Even like these to rail and sweat

Staring upon his sinewy thigh”

A further incident which incensed him involved Hugh Lane, Lady Gregory’s nephew. Lane had amassed an impressive collection of paintings, which he wanted encased in a new gallery bridging the river Liffey; Sir Edwin Lutyens, a British architect, was tasked with designing it. This in turn angered Irish nationalists, who opposed Lutyen’s involvement owing to his nationality. This led to a deluge of verbal and written attacks, against both Lane and the paintings he had collected.

The vituperation of Irish nationalists escalated Yeats’ already brewing animus against the Catholic middle class. Now his dislike was explicitly conveyed in a note attached to some of his poems penned shortly after the Hugh Lane controversy:

“Religious Ireland thinks of divine things as a round of duties separated from life, while political Ireland see the good citizen but as a man who holds to certain opinions. Against all this we have but a few educated men and the remnants of an old traditional culture among the poor. Both were stronger forty years ago, before the rise of our new middle class which made its first public display during the nine years of the Parnellite split, showing how base at moments of excitement are minds without culture.”

Yeats cleverly links the fortune of Ireland’s Gaelic inheritance with the subsistence of Anglo-Irish hegemony, thus allowing him to attack the Catholic Irish whilst simultaneously conferring himself the leeway to posture as a true stalwart of Gaeldom. He grandstanded against Irish Catholics among the rising middle class, whose fortunes inversely correlated with the decline of our culture, which Yeats imputed as causal events. I see what you’re doing Yeats, you crafty Protestant. D.P. Moran discerned your duplicitous intentions; he called you “a crypto-Protestant conman”.

Grattan Freyer speculates that Yeats believed in “leadership by an elite supported by an uncontaminated peasantry ranged against the commercial middle class”. According to Seamus Deane, Standish James O’Grady held views which were akin to Yeats’: “Yet O’Grady does have a version of the potential alliance between peasantry and landlords – later adapted by Yeats – who live in another territory, a Celtic world untainted by actuality, narrativised into legend but not into history, where it is always dawn or twilight, never monotonous daylight”.

Yeats’ dismay is expressed in September 1913, wherein he decries that the Ireland of his dreams, a nation of artistic and cultural vitality, had not come to fruition. For Yeats, the Catholic middle class, owing to their parochial prejudices, had failed to live up to the vision of Tone and Emmet. He laments:

“Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the Grave.”

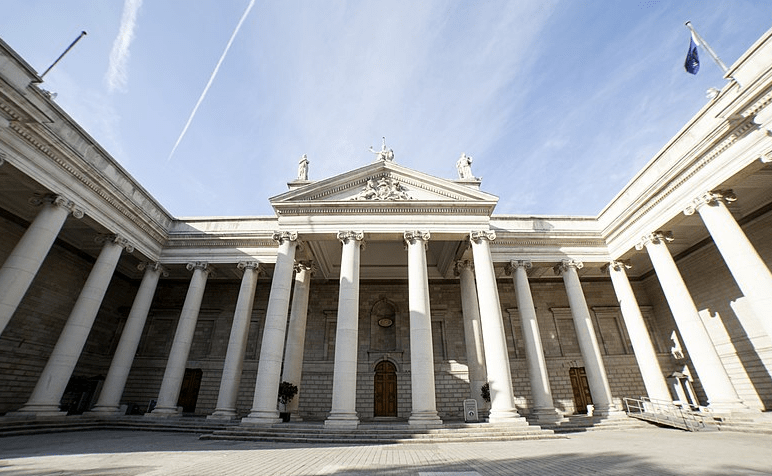

Yeats abstained from political involvement throughout the War of Independence. In the Civil War he favoured the pro-treaty side, and he was appointed a member of the First Seanad. From 1922 onwards Yeats used his platform in the upper chamber of Leinster House to voice his disapproval of legislation that was popular among his foes in the Catholic middle class. His most famous speech, the content of which echoes the arrogance of Berkeley and Swift, was delivered in a Seanad debate regarding divorce, in which he exalted the Anglo-Irish contribution to Irish history:

“I am proud to consider myself a typical man of that minority. We against whom you have done this thing, are no petty people. We are one of the great stocks of Europe. We are the people of Burke; we are the people of Grattan; we are the people of Swift, the people of Emmet, the people of Parnell. We have created the most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence. Yet I do not altogether regret what has happened. I shall be able to find out, if not I, my children will be able to find out whether we have lost our stamina or not. You have defined our position and have given us a popular following. If we have not lost our stamina then your victory will be brief, and your defeat final, and when it comes this nation may be transformed”

Yeats retired from his role in the Seanad in 1928. Shortly thereafter, the Government’s Censorship of Publication’s Bill came before the Seanad. Owing to the Catholic rationale undergirding it, as well as his own consistent commitment to artistic freedom, Yeats swiftly scathed it in the Spectator. He remarked that its only fruitful outcome would be a consolidation of intellectuals on both sides of the Treaty-split in a united front against it.

Conclusion

“A number of writers then arose, headed by Mr. W. B. Yeats, who, for the purposes they set themselves to accomplish, lacked every attribute of genie but perseverance. However, by proclaiming from the house-tops that they were great Irish literary men, they succeeded in attracting that notice from the people of Ireland […] Practically no one in Ireland understands Mr. Yeats or his school; and one could not, I suggest, say anything harder of literary men. Or if a literary man is not appreciated and cannot be understood, of what use is he? He has not served his purpose. The Irish mind, however, was wound down to such a low state that it was in a fit mood to be humbugged by such a school.” – D.P Moran, ‘The Philosophy of Irish Ireland’

A pensive reflection on W.B. Yeats’ thought, insofar as it pertained to Ireland, gives rise to the image of an ouroboros. Yeats began his life as an adversary of Catholics; subsequently he adopted the Republicanism of John O’Leary and embraced an atrophied Gaelic mysticism, suited for his anti-modernist ends. But the autumnal and winter period of his life was marked by a loathing of the Catholic middle class – he returns to the innocent prejudice of youth; the serpent devours its own tail.

The metaphor can be extended, without distortion, to the vacillation of Anglo-Irish perceptions of Irish Catholics throughout the centuries. Originally regarded as ‘base’ and ‘lowly’ by Swift and Berkeley, Gaelic Irishmen were thereafter idolised, thanks to the O’Gradys, for their linear connection to an older, purer civilisation – vestiges remained among pockets of native speakers, those sage custodians of an immemorial inheritance. Yeats came under the influence of O’Grady, but he also foreshadowed a novel tendency that would crystallise in the thought of the stickies and in revisionist historiography: hostility to middle class Irish Catholics.

Have we not returned to the days of Bishop Berkeley? And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards Hibernia to be born?

Fascism is of the left, not the right.